With our archives now 3,500+ articles deep, we’ve decided to republish a classic piece each Friday to help our newer readers discover some of the best, evergreen gems from the past. This article was originally published in June 2013.

Character. Like honor, it’s a word we take for granted and probably have an affinity for, but likely struggle to define and articulate. It’s a word most men desire to have ascribed to them, and yet the standards for its attainment remain rather vague in our modern age.

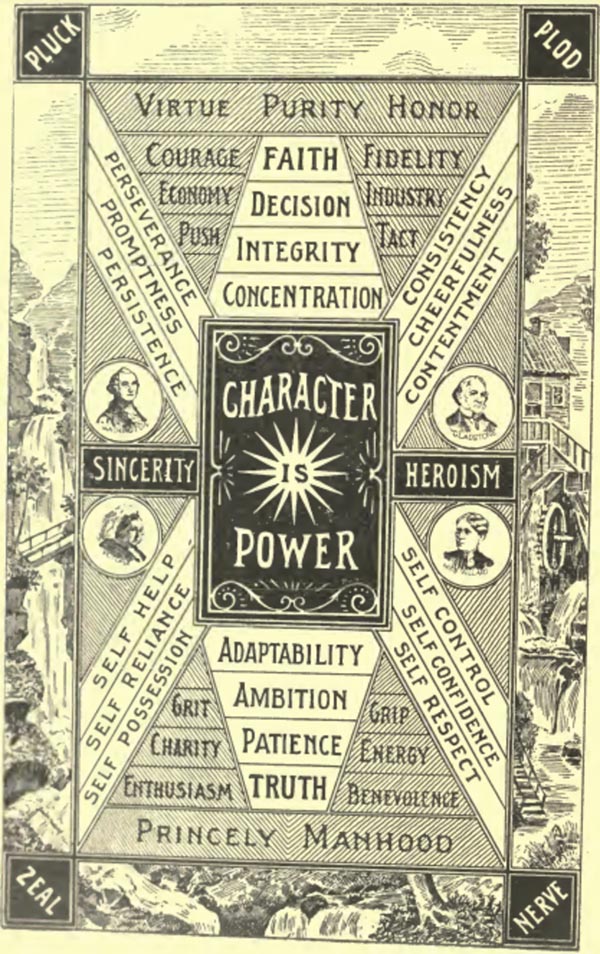

It’s certainly not a word that’s used as much as it once was. Cultural historian Warren Susman researched the rise and fall of the concept of character, tracing its prevalence in literature and the self-improvement manuals and guides popular in different eras. What he found is that the use of the term “character” began in the 17th century and peaked in the 19th – a century, Susman writes, that embodied “a culture of character.” During the 1800s, “character was a key word in the vocabulary of Englishmen and Americans,” and men were spoken of as having strong or weak character, good or bad character, a great deal of character or no character at all. Young people were admonished to cultivate real character, high character, and noble character and told that character was the most priceless thing they could ever attain. Starting at the beginning of the 20th century, however, Susman found that the ideal of character began to be replaced by that of personality

But character and personality are two very different things.

As society shifted from producing to consuming, ideas of what constituted the self began to transform. The rise of psychology, the introduction of mass-produced consumer goods, and the expansion of leisure time offered people new ways of forming their identity and presenting it to the world. In place of defining themselves through the cultivation of virtue, people began to express themselves through hobbies, dress, and material possessions. Susman observed this shift through the changing content of self-improvement manuals, which went from emphasizing moral imperatives and work to personal fulfillment: The vision of self-sacrifice began to yield to that of self-realization.”

While advice manuals of the 19th century (and some of the early 20th as well) emphasized what a man really was and did, the new advice manuals concentrated on what others thought he was and did. In a culture of character, good conduct was thought to spring from a noble heart and mind; with this shift, perception trumped inner intent. Readers were taught how to be charming, control their voice, and make a good impression. A great example of this is Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People from 1936. It focused on how to get people to like you and how to get others to perceive you well versus trying to improve your actual inner moral compass.

Susman argues that the transformation from a culture of character to a culture of personality was ultimately about a shift from “achievement to performance.” Susman illuminates this difference by noting that while the words most associated with character in the nineteenth century were “citizenship, duty, democracy, work, building, golden deeds, outdoor life, conquest, honor, reputation, morals, manners, integrity, and above all, manhood,” the words most associated with personality in the twentieth were “fascinating, stunning, attractive, magnetic, glowing, masterful, creative, dominant, and forceful.”

There’s

No comments:

Post a Comment