We don’t typically think of hospitality as a manly thing. And indeed, it is typically the women in our lives who more often take charge of throwing parties, cooking meals, and preparing the guest room for visitors.

But for thousands of years, offering hospitality was considered an essential part of being a man and living with honor.

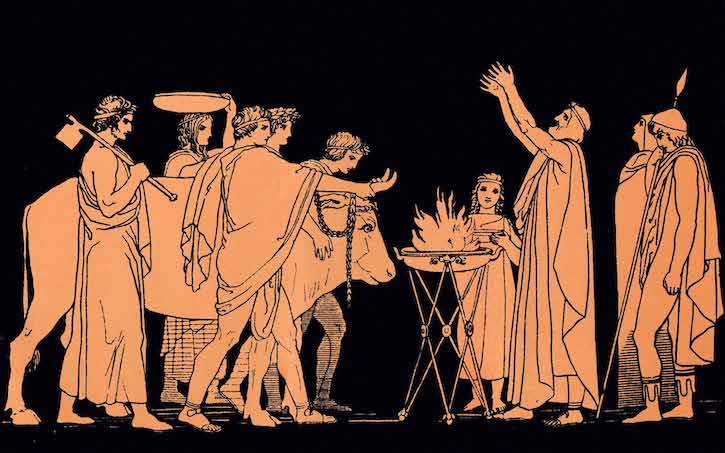

While many ancient cultures had a code of honor which required the practice of hospitality, this code was especially typified by the form it took amongst the Greeks.

The Ancient Greek Idea of Hospitality

In the 1970s, anthropologist Michael Herzfeld studied the culture of masculinity in a small mountainous village on the island of Crete that he dubbed “Glendi” (the name was a pseudonym, to protect the confidentiality of its residents). The Glendiots were a pastoral people who, because of the remoteness and hardscrabble nature of their village, had retained much of the traditional code of manhood that had marked cultures around the world since ancient times. One of the things Herzfeld discovered about that culture was “that the height of eghoismos, self-regard, is a lavish display of hospitality.”

The Glendiots’ emphasis on hospitality traces all the way back to ancient Greece, when it was called xenia. Xenia was an honor-based code of etiquette that concerned the relationship between hosts and guests, especially between hosts and guests who were strangers to each other.

So what did good xenia look like in ancient Greece?

Well, a host was expected to welcome into his home anyone who came knocking. Before a host could even ask a guest his name or where he was from, he was to offer the stranger food, drink, and a bath. Only after the guest finished his meal could the host inquire about the visitor’s identity. After the guest ate, the host was expected to offer him a place to sleep. When he was ready to leave, the host was obligated to give his guest gifts and provide him safe escort to his next destination.

Guests in turn were expected to be courteous and respectful towards their hosts. During their stay, visitors were not to make demands or be a burden. Guests were expected to ply the host and his household with stories from the outside world. The most important expectation was that the guest would offer his host the same hospitable treatment if he ever found himself journeying in the guest’s homeland.

Once you understand the ancient Greek concept of xenia, you’ll start to see it everywhere in ancient Greek texts. The Odyssey is basically the Greek bible on xenia. Pretty much every story in it has something to teach about either neglecting or upholding the tenets of xenia.

Circe turning Odysseus’ men into pigs? Bad xenia.

The cyclops eating Odysseus’ men? Bad xenia.

The Phaeacians giving Odysseus a banquet and gifts? Good xenia.

The suitors mooching off Odysseus while he was gone? Bad xenia.

Why Was Hospitality an Important Part of Male Honor?

While xenia particularly emphasized the importance of treating strangers well, the Greek concept of hospitality encompassed one’s treatment of friends, family, and neighbors as well. And the reason the ancient Greeks (and other ancient peoples) elevated hospitality to a prominent place in the manly code of honor range from the social to the practical to the religious:

Earning/showing status. Manhood has always been a hierarchical dynamic. Men look for ways to raise their status, and for the ancients, one of those ways was through what historian Nigel M. Kennell calls “displays of competitive generosity.”

In setting out ample spreads for strangers and throwing lavish parties and weddings for family and friends, men demonstrated that they had resources, that, among the 3 P’s that traditionally marked the code of manhood — protect, procreate, and provide — they possessed plenty of skill and prowess in that latter category.

“Glendiot hosts not only vie with each other to treat strangers,” Herzfeld observes in The Poetics of Manhood, “they are also engaged in continual competition with one another”:

In the village houses of the Glendiots, meat is often served out of a large cauldron (tsikali) in which it has been cooked by women. Its preparation, however, is again often begun by men, who do the initial cutting of meat with their personal knives.

. . .

A host who serves only a small

No comments:

Post a Comment