Decades ago, society was more bullish on the importance of exercise in weight management. Just go jogging a few times a week, the thinking went, and you’d shed the pounds — never mind that you ended your run by heading to the bagel shop for a big, well-earned, carb-tastic breakfast.

In the last decade, much water has been thrown on the idea of using exercise to manage your weight, and the importance of diet has risen ascendant. Nutritionists and fitness trainers are quick to tell folks that “You can’t outrun your fork!” and “Abs are made in the kitchen!” Which is to say, that when it comes to preventing weight gain, losing the lbs, and keeping lost pounds from coming back, exercising a lot can’t compensate for a poor diet.

Which is perfectly true; diet is the critical factor in weight management. But, as with all cultural trends, once the pendulum on something swings too far in one direction, an overcorrection occurs in which it then swings too far in the other.

What’s gotten lost these days is that exercise is incredibly helpful in achieving and maintaining a healthy weight. While exercise alone (without a modification in diet) is only modestly effective in helping someone lose weight (the more, and more intensely, you exercise, the more effective it becomes), exercise has been shown to be significantly effective in preventing weight gain in the first place, and to be even more important than diet in preventing the regaining of weight after its been lost.

The efficacy of exercise in weight management is due to a number of factors, such as the way it increases lean muscle mass and improves metabolic health. But its most potent factor is one that typically goes unappreciated: the way it regulates appetite.

The Profound Effect of Exercise on Appetite

It’s often assumed that exercise will increase your appetite and make you hungrier. Some people who are trying to lose weight actually avoid it for that very reason.

But as it turns out, active people eat less than inactive people.

In our podcast interview with Dr. Layne Norton, he described a study done “in the 1950s looking at Bengali workers [that] looked at sedentary people, people with a lightly active job, a moderately active job, and a heavy labor job”:

And what they found was from the lightly active to heavily active jobs people pretty much matched their intake without even trying. They just ate more calories and they remained in calorie balance. What they found was the sedentary people actually ate more than every other group except for the heavy labor jobs.

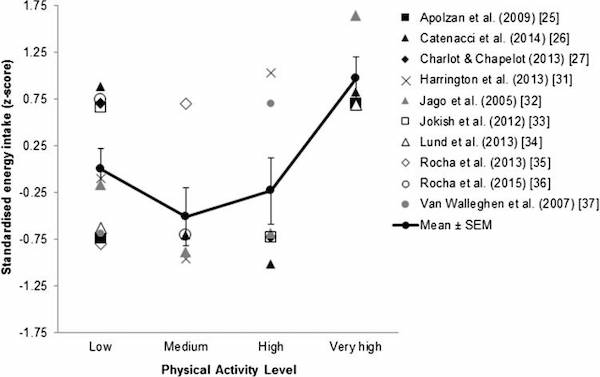

This same result has been born out from more recent studies. As shown in this graph from one, the relationship between physical activity and appetite follows a J-curve:

So to reiterate here: even though they’re inactive, and thus have lower energy intake needs, sedentary folks eat more than even people with high activity levels (the only people they eat less than are those with very high activity levels, who because of the intensity of their activity, obviously have exceptional energy intake requirements). As your level of physical activity increases, so does your ability to match your energy intake with your energy expenditure.

What causes the mismatch between energy expenditure and energy intake for sedentary people, and the healthy coupling between the two for active people?

Well, regular, long-term exercise has been shown to have a kind of paradoxical effect on appetite: it does increase your drive to eat, but, this effect is balanced by an improvement in your appetite sensitivity — your sensitivity to the signals of satiety. So, you may feel a little hungrier overall, but when you sit down to eat, you’re more likely to stop eating when you’re full, and less likely to overeat. As you increase your physical activity, you may eat more, but this increase in caloric intake is matched to your increase in caloric expenditure; you intuitively couple your energy consumption to

No comments:

Post a Comment